This past Saturday, in the small community of Las Araditas in El Paisnal, El Salvador, the rural communities from the municipalities of El Paisnal, Aguilares, San Pablo Tacachico and Suchitoto, came together to commemorate their martyrs. On September 29th, 1979, thirty years ago, community leaders Felix Garcia, Patricia “Ticha” Puertas, Apolinario “Polin” Serrano and Jose Lopez were killed by the armed forces when their car was pulled over on the road to Santa Ana. Feliz, Ticha and Polin were all leaders of the the Christian Federation for Salvadoran Peasants-Union of Peasant Workers. Inspired by the theology of liberation and the words of priests such as Rutilio Grande, these illiterate peasants organized themselves to fight for their rights. Their deaths were mourned by all those who knew and loved them, including Monseñor Romero who was still alive at the time of their deaths.

Now, thirty years later, one can see the impact that these martyrs had on the population that lives below the Guazapa hill. SHARE counterpart, UCRES: United Communities of Northern San Salvador and La Libertad, planned the event with the support of the mayor of El Paisnal and pickup trucks full of people from over twenty communities, from as far as Chalatenango showed up to participate in the commemoration event. UCRES President Alex along with community leader Guadalupe and Salvadoran Supreme Court Magistrate, Mirna Perla, led the people in singing the “Hymn of Unity” with its cry of “the people united, will never be defeated.” After all participating communities were welcomed, and the local parish priest talked a little about the history of the organized communities in the region, the people participated in a a mass celebrated by the two local Catholic priest and three Lutheran ministers. The mass was followed by lunch and live music. One of the most inspiring part of the entire commemoration was the number of youth in atte

ndance. Youth who were not even born at the time that these community leaders were killed, but have been told the stories over and over by their family members. In a country where events from the war are often glossed over or ignored by mainstream culture, the collective memory of the organized communities steps up to keep the spirit of their martyrs. So much so that the lives of these four peasants are still being celebrated by hundreds of people, thirty years after their deaths.

ndance. Youth who were not even born at the time that these community leaders were killed, but have been told the stories over and over by their family members. In a country where events from the war are often glossed over or ignored by mainstream culture, the collective memory of the organized communities steps up to keep the spirit of their martyrs. So much so that the lives of these four peasants are still being celebrated by hundreds of people, thirty years after their deaths.Laura Hershberger, SHARE Grassroots Solidarity Coordinator

Guazapa martyr Apolinario Serrano “Polin” as remembered in the biography of Oscar Romero “Memories in Mosaic”

HE ARRIVED ONE DAY in a big rush, making great sweeps with his visored cap and flapping his hands as was his habit. "Ay, my head's so full already, nothing more will fit in it!!"

He understood that a head was like a warehouse to store ideas in. And he had already learned so many new things that even that prodigious memory of his wasn't enough to remember everything.

"I need to learn to read and write. To be able to tore more!" For three years there had been resistance to Chamba and Cauche teaching him literacy. But now that it was decided, he was there within three days. No one read as nimbly as he did.

Polín. Apolinario Serrano. From El Líbano canton, at the foot of the Guazapa hill. A cane cutter since he was a kid, with fingers deformed from so many harvests and so much machete. A nomadic hog raiser from over near Suchitoto with his network of connections that only he knew about. One of the hundreds of Delegates of the Word born with the experience of the Aguilares parish. And, without doubt, the most brilliant of them all.

And soon thereafter, the most inspired of El Salvador's peasant leaders. What a special kind of leader Polín was! He could put any audience in the palm of his hand. He laced his speeches with proverbs, with jokes, with stories from the Bible. And more than anything, with reality.

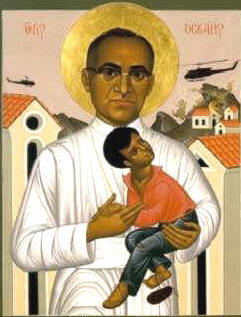

The Monseñor Romero Coalition, of which the SHARE Foundation is a member, wishes to inform the Salvadoran civil society and the international community of the launching of a citizens campaign entitled "MONSEÑOR ROMERO: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND HOPE."

The Monseñor Romero Coalition, of which the SHARE Foundation is a member, wishes to inform the Salvadoran civil society and the international community of the launching of a citizens campaign entitled "MONSEÑOR ROMERO: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND HOPE."