http://picasaweb.google.com/PFlajole/SanVicente?feat=email#

After being hit by heavy rains of November 7th, which killed almost two hundred people and destroyed around 10,000 homes, SHARE put out the word that emergency relief was needed and that we would be fundraising to provide immediate and long term assistance to those affected communities. We were overwhelmed by the generous response of individuals, groups and entire communities in the States who wanted to provide assistance to those suffering from the loss of their homes and of their loved ones. We would like to thank all those who have contributed and continue to contribute to those affected by the heavy rains. From the donations that we have collected we have been able to contribute support four different regions of the country. In La Paz, we worked through the organization ISD to give $5,000 for mattresses, bed sheets and blankets, and food packets. In San Martin we were able to give $

After being hit by heavy rains of November 7th, which killed almost two hundred people and destroyed around 10,000 homes, SHARE put out the word that emergency relief was needed and that we would be fundraising to provide immediate and long term assistance to those affected communities. We were overwhelmed by the generous response of individuals, groups and entire communities in the States who wanted to provide assistance to those suffering from the loss of their homes and of their loved ones. We would like to thank all those who have contributed and continue to contribute to those affected by the heavy rains. From the donations that we have collected we have been able to contribute support four different regions of the country. In La Paz, we worked through the organization ISD to give $5,000 for mattresses, bed sheets and blankets, and food packets. In San Martin we were able to give $ 5,000 to the organization REDES in order to buy personal hygiene packets to affected families. In Aguilares and El Paisnal we worked through our long time sistering counterpart UCRES to provide $7,000 to buy stoves and gas tanks. And in Southern La Libertad we worked with CORDES and CRIPDES SUR to distribute $5,000 worth of mattresses, bed sheets and blankets and food packets.

5,000 to the organization REDES in order to buy personal hygiene packets to affected families. In Aguilares and El Paisnal we worked through our long time sistering counterpart UCRES to provide $7,000 to buy stoves and gas tanks. And in Southern La Libertad we worked with CORDES and CRIPDES SUR to distribute $5,000 worth of mattresses, bed sheets and blankets and food packets. December 5th to first accompany SHARE to CRIPDES and CORDES South in La Libertad to pass out mattresses, bed sheets and food packets to 177 affected families in the communities of San Diego and Santa Cruz. We then travelled to CORDES UCRES in Aguilares and El Paisnal for the group to distribute stoves to 140 families. The mayor of Aguilares contributed to the donation by including a tank of gas with each stove given out.

December 5th to first accompany SHARE to CRIPDES and CORDES South in La Libertad to pass out mattresses, bed sheets and food packets to 177 affected families in the communities of San Diego and Santa Cruz. We then travelled to CORDES UCRES in Aguilares and El Paisnal for the group to distribute stoves to 140 families. The mayor of Aguilares contributed to the donation by including a tank of gas with each stove given out.

Part 1: The History of El Salvador

My name is Marina Peña, I'm the director of SHARE here in El Salvador. Welcome to this small country. El Salvador is a country with much history: much history of struggle and hope. Despite the critical situation in which we live, Salvadorans don't lose the hope of living in a better country. I'm going to tell you a little about the principal problems that we have in our country. In the subject of economics, we are confronting four main problems. The first problem which is a historic one is the problem of concentration of wealth. The wealth is in the hands of a small number of families who are very rich while the majority of the population is very poor.

This problem has provoked various movements throughout our history coming from the classes that feel marginalized acting out against the classes who have the power. For exa mple this happened after the independence from the Spanish state as it was Spain that governed us for hundreds of years. You remember that Christopher Columbus came and colonized us at the end of the 1400's. So Spain dominated us for 300 long years and during that time they robbed from us the riches in this areas mostly being gold. The eliminated our culture. There is very little indigenous culture in our country and there used to be so much more. They destroyed the language that our indigenous spoke which was Nahuatl, and the majority of the cities they found they also destroyed. The only thing we have left now are buildings or structures that the indigenous were able to hide and the Spanish weren't able to detect. They also imposed their religion upon us over the religious beliefs that are ancestors had. It was in 1811 when the first independence struggles started to happen in Central America and it was 1821 when they achieved independence from Spain. But those who took power after independence continued e

mple this happened after the independence from the Spanish state as it was Spain that governed us for hundreds of years. You remember that Christopher Columbus came and colonized us at the end of the 1400's. So Spain dominated us for 300 long years and during that time they robbed from us the riches in this areas mostly being gold. The eliminated our culture. There is very little indigenous culture in our country and there used to be so much more. They destroyed the language that our indigenous spoke which was Nahuatl, and the majority of the cities they found they also destroyed. The only thing we have left now are buildings or structures that the indigenous were able to hide and the Spanish weren't able to detect. They also imposed their religion upon us over the religious beliefs that are ancestors had. It was in 1811 when the first independence struggles started to happen in Central America and it was 1821 when they achieved independence from Spain. But those who took power after independence continued e xploiting the poor in our country. The people who took control where what we call Creoles, the children of the Spanish, who substituted Spanish power. They maintained a regimen of exploitation against the majority who were people who lived in the countryside, campesinos and indigenous. And so because of this exploitation and because they were kicking many indigenous off their land, there was an uprising of indigenous who were protesting against the extreme poverty they lived in and being kicked off their land. This uprising was crushed by the army, through many political assassinations, the uprising was put down by throwing the indigenous in jail or murdering them.

xploiting the poor in our country. The people who took control where what we call Creoles, the children of the Spanish, who substituted Spanish power. They maintained a regimen of exploitation against the majority who were people who lived in the countryside, campesinos and indigenous. And so because of this exploitation and because they were kicking many indigenous off their land, there was an uprising of indigenous who were protesting against the extreme poverty they lived in and being kicked off their land. This uprising was crushed by the army, through many political assassinations, the uprising was put down by throwing the indigenous in jail or murdering them.

But fear can only keep people down for so long and in 1932 there was second uprising but this ti me it wasn't only the indigenous, but all campesinos. This campesino movement was accompaniment by the Communist party in El Salvador that had only been around in El Salvador for two years and one of its leaders was a man named Farabundo Marti. The majority of this happened in the western part of the country in Sonsonate, Santa Ana and Ahuachapan. From this uprising rose up leaders like Farabundo Marti and two other students named Luna and Zapata. The three of them studied at the National University here in San Salvador. This uprising was once again crushed by the army and there was a great massacre in the western part of the county and it is estimated that there were about 30,000 indigenous and campesinos killed in January and February of 1932.

me it wasn't only the indigenous, but all campesinos. This campesino movement was accompaniment by the Communist party in El Salvador that had only been around in El Salvador for two years and one of its leaders was a man named Farabundo Marti. The majority of this happened in the western part of the country in Sonsonate, Santa Ana and Ahuachapan. From this uprising rose up leaders like Farabundo Marti and two other students named Luna and Zapata. The three of them studied at the National University here in San Salvador. This uprising was once again crushed by the army and there was a great massacre in the western part of the county and it is estimated that there were about 30,000 indigenous and campesinos killed in January and February of 1932.

Because the basic problems of social injustice were not solved, there is another movement that comes in 1970 when workers and campesinos began to demand better salaries and social justice. It started around 1972 and until 1979 we see a wave of organization that started in the campo and moved to the city where artisans, workers and farmers came together and started to organi ze. This movement was inspired by the Cuban revolution and the Nicaraguan Sandinista revolution in 1979, but the principle motivation was the social injustice in place in our country. It was in this context that Monseñor Romero, the four churchwomen and approximately 80,000 other people were killed from about 1980-1992. In 1980, the civil war begins and it lasted until the peace accords in 1992. As I said, this war cost us 80,000 deaths and about 8,000 disappeared, hundreds of political prisoners and of course many people who left the country due to political persecution. It was in these years that many Salvadorans left our country and went to live in the states due to oppression. In those years to say something like, beans are expensive or salaries are low was to mark yourself as a communist and to be killed. In 1992 they signed the peace accords which ended the armed conflict. But the problems of social injustices and the concentration of wealth was not resolved. And this is a problem that has persisted and is now even more pronounced.

ze. This movement was inspired by the Cuban revolution and the Nicaraguan Sandinista revolution in 1979, but the principle motivation was the social injustice in place in our country. It was in this context that Monseñor Romero, the four churchwomen and approximately 80,000 other people were killed from about 1980-1992. In 1980, the civil war begins and it lasted until the peace accords in 1992. As I said, this war cost us 80,000 deaths and about 8,000 disappeared, hundreds of political prisoners and of course many people who left the country due to political persecution. It was in these years that many Salvadorans left our country and went to live in the states due to oppression. In those years to say something like, beans are expensive or salaries are low was to mark yourself as a communist and to be killed. In 1992 they signed the peace accords which ended the armed conflict. But the problems of social injustices and the concentration of wealth was not resolved. And this is a problem that has persisted and is now even more pronounced.

Photo 1: Christopher Columbus, conquistador

Photo 2: Anastasio Aquino, Leader in the indigenous uprising of 1833

Photo 3: Farabundo Marti, Leader of campesino uprising in 1932

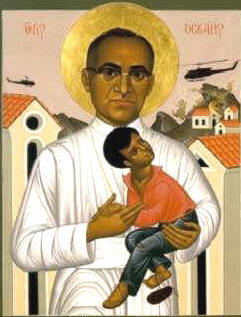

Photo 4: Oscar Romero, assassinated Archbishop

Part 2: The Economy and Violence in El Salvador

They say in our country that 10 percent of the population has 90 percent of the wealth and 10 percent of the wealth is distributed among 90 percent of the population. This is what provokes the majority of the problems that we have in our country like d elinquency and violence. Its what provokes the social struggles. Just a few minutes before I entered this room, the police were chasing a thief down the street, which is a common sight in our country. This is not just chance, its a product of a long history of social problems that have not been resolved. In the last 20 years under the ARENA government, this inequality has become worse. But apart from this, we have problems with the entity with whom we do the majority of our business and that is the United States. The economy of El Salvador is in crisis right now in large part due to the poor administration of the ARENA government of the past twenty years. But also, in part because of the economic crisis that is affecting the United States and that now affects the entire world. But it affects us a little more directly for three reasons. First because the majority of production in El Salvador is

elinquency and violence. Its what provokes the social struggles. Just a few minutes before I entered this room, the police were chasing a thief down the street, which is a common sight in our country. This is not just chance, its a product of a long history of social problems that have not been resolved. In the last 20 years under the ARENA government, this inequality has become worse. But apart from this, we have problems with the entity with whom we do the majority of our business and that is the United States. The economy of El Salvador is in crisis right now in large part due to the poor administration of the ARENA government of the past twenty years. But also, in part because of the economic crisis that is affecting the United States and that now affects the entire world. But it affects us a little more directly for three reasons. First because the majority of production in El Salvador is sold to the United States. 80 percent of the products that El Salvador export is from the United States. Of course if the United States isn't buying as much as it did before, we won't sell as much, and this affects our economy. The principal product that the United States buys is textiles, but also some traditional Salvador products because we have two and a half million people from our country living in the United States.

sold to the United States. 80 percent of the products that El Salvador export is from the United States. Of course if the United States isn't buying as much as it did before, we won't sell as much, and this affects our economy. The principal product that the United States buys is textiles, but also some traditional Salvador products because we have two and a half million people from our country living in the United States.

Now we come to the second aspect, those two and a half million Salvadorans send back 3 billion dollars annually in remittances to their families in El Salvador. And those 3 billion dollars that immigrants send to their families, balances our the commercial spending here in El Salvador. The commercial balance is what a country looks to obtain in its trading policies. You want to balance out what you export and import and you look to sell more than you buy so that you gain money. All countries in the world have this economic index to rate their economy. Well here in El Salvador we always have a deficit in our economy because we always buy more than we sell. In El Salvador, the only way that we have achieved an equilibrium is from the remittances that Salvadorans in the states send back to their family here. But many Salvadorans in the United States work in constructions, one of the sectors most affected by the crisis. And the effect of that is that the remittances have lowered in the last two years. So our economy is slowly sinking because we are selling less to the United States and we are receiving less in remittances.

to obtain in its trading policies. You want to balance out what you export and import and you look to sell more than you buy so that you gain money. All countries in the world have this economic index to rate their economy. Well here in El Salvador we always have a deficit in our economy because we always buy more than we sell. In El Salvador, the only way that we have achieved an equilibrium is from the remittances that Salvadorans in the states send back to their family here. But many Salvadorans in the United States work in constructions, one of the sectors most affected by the crisis. And the effect of that is that the remittances have lowered in the last two years. So our economy is slowly sinking because we are selling less to the United States and we are receiving less in remittances.

The third economic problem that we have is that we are dollarized, which means we use the US dollar. So we don't have a monetary policy because we don't have our own currency. This limits the government from making certain policies that would allow for an equilibrium in our economy that we might have if we weren't dollarized. This also makes us more vulnerable to the depreciation of the dollar on world scales, like when the dollar loses value. The result is that our economy is in deceleration, which means that the level of growth in El Salvador is  negative 2%. This of course, aggravates our social problems that are already in a grave situation here in our country. For example there is more unemployment, the health care system is in crisis, there is not enough medicine, hospitals or medical staff to deal with the crisis. On top of all of this comes H1N1 which affects the poorest sectors of the country. So it becomes a vicious cycle, there are no jobs, so there is no money and people get sick and there are not adequate hospitals, and it just continues. And of course it makes other problems worse such as violence and crime.

negative 2%. This of course, aggravates our social problems that are already in a grave situation here in our country. For example there is more unemployment, the health care system is in crisis, there is not enough medicine, hospitals or medical staff to deal with the crisis. On top of all of this comes H1N1 which affects the poorest sectors of the country. So it becomes a vicious cycle, there are no jobs, so there is no money and people get sick and there are not adequate hospitals, and it just continues. And of course it makes other problems worse such as violence and crime.

Our country suffers from an epidemic of violence. We currently have a level of violence that we had while we were at war. We have an average of 11 deaths a day in our country. I've heard of some places in the States where there are about five violent deaths a year and in our country we have 11 violent deaths a day, the majority of whom are young men, but also young women. This problem has made us the most violent  country in all of Latin America and one of the ten most dangerous countries in the world. You all should know also that violence can become business, in our country there are people interested in violence continuing. Here there are many big businesses that run security companies, and they basically have their own armies in our country. For example a private security business can have around 5,000 people who are armed, for these businesses its good for them that there is violence. If this country were to become peaceful, there would be no use for the security businesses. You all have probably noticed because it is very different from the States here, that every business has an armed man standing outside the door. And all the neighborhoods are surrounded by armed men. Everyone one of us who live in this country can pay for our guard. I pay twelve dollars a month for guard in the neighborhood where I live. Thats how the world works here, someone is making money of the violence. Therefore, it is in their interest that violence continues. During the ARENA government, violence was basically promoted. Now they are making an effort to make policies that promote violence prevention. But of course we won't see the results of the policies immediately, rather in coming years.

country in all of Latin America and one of the ten most dangerous countries in the world. You all should know also that violence can become business, in our country there are people interested in violence continuing. Here there are many big businesses that run security companies, and they basically have their own armies in our country. For example a private security business can have around 5,000 people who are armed, for these businesses its good for them that there is violence. If this country were to become peaceful, there would be no use for the security businesses. You all have probably noticed because it is very different from the States here, that every business has an armed man standing outside the door. And all the neighborhoods are surrounded by armed men. Everyone one of us who live in this country can pay for our guard. I pay twelve dollars a month for guard in the neighborhood where I live. Thats how the world works here, someone is making money of the violence. Therefore, it is in their interest that violence continues. During the ARENA government, violence was basically promoted. Now they are making an effort to make policies that promote violence prevention. But of course we won't see the results of the policies immediately, rather in coming years.

Part 3: Agriculture in El Salvador

Another one of the large problems we have is the lack of employment in the campo. This was  provoked by the fact that in 20 years of ARENA government, they destroyed agriculture in our country. There was a man who was the President of El Salvador named Cristiani, he has a business in which he sells agricultural seeds and products and he is the only one who sells seeds in this country. So in 1992 when they started to implement the neo-liberal model in our country, they negotiated with agricultural producers in the United States, that El Salvador would dedicate itself to the maquila industry. So that it wouldn't be necessary to have agricultural producers here in El Salvador, it would be cheaper to buy the corn and the beans from the United States

provoked by the fact that in 20 years of ARENA government, they destroyed agriculture in our country. There was a man who was the President of El Salvador named Cristiani, he has a business in which he sells agricultural seeds and products and he is the only one who sells seeds in this country. So in 1992 when they started to implement the neo-liberal model in our country, they negotiated with agricultural producers in the United States, that El Salvador would dedicate itself to the maquila industry. So that it wouldn't be necessary to have agricultural producers here in El Salvador, it would be cheaper to buy the corn and the beans from the United States and bring it here. Of course, it was cheaper because agricultural companies in the States are subsidized by the government. So they can sell their grains at a much cheaper price. This agreement made between Cristiani and the agricultural businesses in the States, forced small farmers into bankruptcy. People stopped cultivating, because they were spending money in seeds sold by Cristiani and agricultural supplies but when they went to sell the product, the prices were so low that they lost money, it put them in debt, they didn't even cover their costs. What many campesinos did was to sell their land and go to the United States undocumented. There are entire towns of Salvadorans living in the United States for this reason. Here in the Eastern zone in Morazan, San Miguel y La Union in El Salvador, where entire populations have left together to go to the States, but they left as a result of policies here.

and bring it here. Of course, it was cheaper because agricultural companies in the States are subsidized by the government. So they can sell their grains at a much cheaper price. This agreement made between Cristiani and the agricultural businesses in the States, forced small farmers into bankruptcy. People stopped cultivating, because they were spending money in seeds sold by Cristiani and agricultural supplies but when they went to sell the product, the prices were so low that they lost money, it put them in debt, they didn't even cover their costs. What many campesinos did was to sell their land and go to the United States undocumented. There are entire towns of Salvadorans living in the United States for this reason. Here in the Eastern zone in Morazan, San Miguel y La Union in El Salvador, where entire populations have left together to go to the States, but they left as a result of policies here.

What happens when a country can't produce its own food? It becomes very vulnerable and when the the United Nations World Food Program announced that there was a world food crisis, they started to think what is going to happen to the countries that don't even produce their own food? Like El Salvador. In 2005, when Hurricane Stan flooded farm fields in all of Central America, we had a food crisis. For example we buy vegetables from Guatemala and Honduras and meat and beans in Nicaragua. So when Stan came through and crops were lost, those countries wanted to save what they produced for their own people, they didn't want to sell to us. Here in El Salvador where there is no longer food production, there was as great crisis. The basic nutrition of our country is beans and corn. In 2005, the beans cost between 45 cents and 50 cents per pound, but after this crisis the price of beans shot up to 1.25 a pound. In our country there are families that live on a dollar a day, so those families couldn't even buy beans. What does that mean? That these families are condemned to die of hunger. And that is one of the big problems we have with agriculture. Before the Civil, 19 percent of the gross domestic product was agriculture. In 2005, agriculture represented about 1% of our GDP. That goes to show how ARENA governments destroyed the agricultural sector and that is one of the great jobs that this new government has, to reactivate the agriculture, because it is the life and work of the campesino population.

flooded farm fields in all of Central America, we had a food crisis. For example we buy vegetables from Guatemala and Honduras and meat and beans in Nicaragua. So when Stan came through and crops were lost, those countries wanted to save what they produced for their own people, they didn't want to sell to us. Here in El Salvador where there is no longer food production, there was as great crisis. The basic nutrition of our country is beans and corn. In 2005, the beans cost between 45 cents and 50 cents per pound, but after this crisis the price of beans shot up to 1.25 a pound. In our country there are families that live on a dollar a day, so those families couldn't even buy beans. What does that mean? That these families are condemned to die of hunger. And that is one of the big problems we have with agriculture. Before the Civil, 19 percent of the gross domestic product was agriculture. In 2005, agriculture represented about 1% of our GDP. That goes to show how ARENA governments destroyed the agricultural sector and that is one of the great jobs that this new government has, to reactivate the agriculture, because it is the life and work of the campesino population.

Another problem that we have in agriculture is the excessive use of chemicals. In our country before the war, they cultivated cotton, it is a type of crop that demands a lot of chemicals to grow it. During the war the production of cotton basically disappeared. However, the poison from the chemicals is showing up 40 years later. The chemical used to grow cotton falls into the earth but it isn't absorbed by the earth, but humans can absorb it and it has been poisoning our bodies. Women tend to hold the poison in the mammary glands, so that when a woman has a child and breast-feeds, she is passing poison to her child. This means that the effect of this poison isn't just the population of forty years ago, but also future generations. In Tecoluca, San Vicente, last week, a man who worked with us on the Seeds of Hope program died of kidney failure. That is the affects of the chemicals used to plant cotton. Don Lucio had started to work with organic products, but he was already sick and now he is dead. The region of Tecoluca is an area where there is a high number of kidney problems due to use of chemicals in the

Another problem that we have in agriculture is the excessive use of chemicals. In our country before the war, they cultivated cotton, it is a type of crop that demands a lot of chemicals to grow it. During the war the production of cotton basically disappeared. However, the poison from the chemicals is showing up 40 years later. The chemical used to grow cotton falls into the earth but it isn't absorbed by the earth, but humans can absorb it and it has been poisoning our bodies. Women tend to hold the poison in the mammary glands, so that when a woman has a child and breast-feeds, she is passing poison to her child. This means that the effect of this poison isn't just the population of forty years ago, but also future generations. In Tecoluca, San Vicente, last week, a man who worked with us on the Seeds of Hope program died of kidney failure. That is the affects of the chemicals used to plant cotton. Don Lucio had started to work with organic products, but he was already sick and now he is dead. The region of Tecoluca is an area where there is a high number of kidney problems due to use of chemicals in the

Photo 1: Alfredo Cristiani

Photo 4: Don Lucio with his organic corn

But elections carried out under a state of emergency, with visible military and police presence, by a government installed by coup, with a significant movement opposed to the coup calling for abstention, and with the deposed President still holed up in the center of the capital city in the Brazilian Embassy, are no cause for celebration. As we wrote to the State Department on November 24th, “a cloud of intimidation and restrictions on assembly and free speech affect the climate in which these elections take place… basic conditions do not exist for free, fair and transparent elections in Honduras.”

The United States’ apparent eagerness to accept the elections and move on has put it at odds with many Latin American governments. “Latin American governments accused the administration of putting pragmatism over principle and of siding with Honduran military officers and business interests whose goal was to use the elections to legitimize the coup,” wrote Ginger Thompson in the New York Times.San Salvador, El Salvador

Salvadorans from every segment of society gathered here Nov. 14- 16 to commemorate the 1989 murders of six Jesuits, and their housekeeper and her daughter.

Many used local events to reflect on El Salvador's progress since the end of the country's civil war in 1992.

It was 20 years ago that a Salvadoran military unit broke into the grounds of Central American University, brutally killing Jesuits Ignacio Ellacuría, Ignacio Martín Baró, Segundo Montes, Joaquín López y López, Amando López and Juan Ramón Moreno, as well as their housekeeper, Elba Ramos, and her daughter, Celina.

At the entrance to the university, only a short walk from the courtyard where the priests and the women were executed and where they are buried in the university's chapel, students collected supplies to contribute to disaster relief efforts after heavy rains Nov. 8 that led to mudslides, killing 160 people and leaving more than 12,000 homeless.

Carrying out the university commitment to social justice, several noted, is one way students could remember the Jesuits. “This is what they stood for, helping the poor,” one said.

Please receive our greetings!

You may have been reading our eNewsletter updates on the situation in El Salvador following the destruction wrecked by Hurricane Ida. As you might recall from those communications, SHARE is partnering with counterparts in three regions of the country that experienced significant destruction from the flood waters. Just yesterday, I approved three initial projects, worth approximately $17,000 that will provide mattresses, blankets, and basic food items (beans, rice, oil, flour, and drinking water) to an estimated 600 families (or approximately 2700 individuals) in three municipalities.

Clearly, this is an important beginning, but it is only a beginning. The numbers of people affected by Ida continue to rise as the reports from the National Civil Protection System are updated each day. As of yesterday, nearly 15,000 people were reported in temporary shelter settings. It is important to note here that this number does not even begin to take into consideration those who set up rudimentary structures near their homes in order to protect what may have been left behind by the storm and to begin the reconstruction/restoration process.

(Photo by Laura Hershberger, SHARE-El Salvador of a makeshift shelter where two boys from La Florida live with their family adjacent to where the home once was)

During this season of expressing our gratitude, we can extend our thanks to those who have touched our hearts and spirits during our visits, and who now need us to offer our support in a concrete way. Please consider making a secure online gift via our website DONATE HERE or by sending a check to

Share Foundation - Building a New El Salvador Today

P.O. Box 209620

Washington, DC 20017

With gratitude for your companionship as we continue reaching out to those in great need,

José

José Artiga

Executive DirectorWhile the National Hurricane Center in the United States has downgraded Hurricane Ida to a Tropical Storm, El Salvador has experienced the full brunt of hurricane force winds and rain. Over the weekend, the storm destroyed more than 7,000 homes and damaged many more. The most recent data, reported this morning in the Prensa Gráfica, indicates that approximately 130 people have been killed by the storm, and thousands more injured. This total is sure to rise as emergency relief workers continue to work their way through damaged buildings and areas that have experienced landslides.

The community of Verapaz in the department of San Vicente was left badly damaged by mud, rocks and derby after a mudslide from the San Vicente Volcano. Because the heavy rains rapidly made the land on the foothills of the volcano quite unstable, water quickly engulfed much of the town and many people did not have time to prepare or escape.

As is often the case in these sorts of situations, the most immediate problems include access to emergency shelter, access to potable water, and food. SHARE Foundation, in collaboration with its partners in the three departments of San Salvador, La Paz and San Vicente, will be working to provide emergency relief. This will include distribution of plastic sheeting and wood for temporary housing; food and water.

We ask that you lend your support to this effort by making a contribution for emergency relief in response to Hurricane Ida. You can do this by way of a secure online donation via our website or by mailing a check to:

SHARE Foundation

P.O. Box 29620

Washington, DC 20017 (please write Hurricane Ida relief in the memo line)

Other ways you can help:

-Organize fundraising efforts within your local churches and other community groups.

-Pray for the victims of Hurricane Ida and their family members affected by this weekend’s tragedy

Please do not hesitate to call our office at 202.319.5540 or send an email to jose@share-elsalvador.org if you have any questions.

As always, thank you for your continued solidarity and partnerships. We cannot do this without you.

WOLA is pleased to see that H.Res. 761, introduced by Rep. Jim McGovern and 33 co-sponsors, was approved today in the U.S. House of Representatives. This resolution remembers and commemorates the lives and work of the six Jesuit priests and two women who were murdered in El Salvador nearly twenty years ago. On Nov. 16, 1989, armed men burst into the Jesuit residence at the University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador, killing the six Jesuit priests who were there, along with the community’s cook and her daughter.

WOLA is pleased to see that H.Res. 761, introduced by Rep. Jim McGovern and 33 co-sponsors, was approved today in the U.S. House of Representatives. This resolution remembers and commemorates the lives and work of the six Jesuit priests and two women who were murdered in El Salvador nearly twenty years ago. On Nov. 16, 1989, armed men burst into the Jesuit residence at the University of Central America (UCA) in San Salvador, killing the six Jesuit priests who were there, along with the community’s cook and her daughter.

More than 70,000 died during El Salvador’s civil war, the vast majority of whom were civilians killed by the Salvadoran armed forces and paramilitary death squads. The Jesuit case galvanized an outcry for human rights and justice from the international community, played a key role in shifting opinions in the U.S. Congress, and helped to spark the peace process that brought the civil war to an end. WOLA is pleased to see the Congress commemorating this important historical moment, and to see that the resolution urges the United States today to collaborate with El Salvador's new government on the unfinished tasks to which the Jesuits were committed - the "efforts to reduce poverty and hunger and to promote educational opportunity, human rights, the rule of law and social equity for the people of El Salvador."

To see the resolution click here.

ndance. Youth who were not even born at the time that these community leaders were killed, but have been told the stories over and over by their family members. In a country where events from the war are often glossed over or ignored by mainstream culture, the collective memory of the organized communities steps up to keep the spirit of their martyrs. So much so that the lives of these four peasants are still being celebrated by hundreds of people, thirty years after their deaths.

ndance. Youth who were not even born at the time that these community leaders were killed, but have been told the stories over and over by their family members. In a country where events from the war are often glossed over or ignored by mainstream culture, the collective memory of the organized communities steps up to keep the spirit of their martyrs. So much so that the lives of these four peasants are still being celebrated by hundreds of people, thirty years after their deaths.Laura Hershberger, SHARE Grassroots Solidarity Coordinator

Guazapa martyr Apolinario Serrano “Polin” as remembered in the biography of Oscar Romero “Memories in Mosaic”

HE ARRIVED ONE DAY in a big rush, making great sweeps with his visored cap and flapping his hands as was his habit. "Ay, my head's so full already, nothing more will fit in it!!"

He understood that a head was like a warehouse to store ideas in. And he had already learned so many new things that even that prodigious memory of his wasn't enough to remember everything.

"I need to learn to read and write. To be able to tore more!" For three years there had been resistance to Chamba and Cauche teaching him literacy. But now that it was decided, he was there within three days. No one read as nimbly as he did.

Polín. Apolinario Serrano. From El Líbano canton, at the foot of the Guazapa hill. A cane cutter since he was a kid, with fingers deformed from so many harvests and so much machete. A nomadic hog raiser from over near Suchitoto with his network of connections that only he knew about. One of the hundreds of Delegates of the Word born with the experience of the Aguilares parish. And, without doubt, the most brilliant of them all.

And soon thereafter, the most inspired of El Salvador's peasant leaders. What a special kind of leader Polín was! He could put any audience in the palm of his hand. He laced his speeches with proverbs, with jokes, with stories from the Bible. And more than anything, with reality.

Salvadorans Seek a Voice To Match Their Numbers

Summit Aims to Raise Political Visibility

By N.C. AizenmanWashington Post Staff Writer

Thursday,

September 24, 2009

For nearly three decades Salvadoran immigrants have been among the nation's

most organized newcomers, founding clubs to raise money for schools back home, establishing medical clinics for new arrivals and battling in Congress and courts to gain legal status for tens of thousands of political dissidents who fled persecution by the U.S.-backed government during El Salvador's civil war in the 1980s.

Yet, even as Salvadoran immigrants and Americans of Salvadoran descent have grown to number 1.6 million -- essentially tying them with Cubans as the nation's third largest Latino group -- they have mostly shied from direct participation in U.S. politics.

About 150 of the community's most prominent leaders from across the country gathered in Washington to change that Wednesday.

"This conference is about stepping it up to another level of visibility, performance and power," said Maryland Del. Ana Sol Gutierrez (D-Montgomery), a co-organizer of the First Salvadoran American Leadership Summit.

"When we first came to the United States, it was just about survival, so that's what our organizations focused on," Salvadoran-born Gutierrez said. "Now we have a community that has evolved, but I think we're kind of stuck in that service model. . . . We have to either create new political institutions, or we have to expand those current organizations so they also play a political role."

Conference participants plan to lobby more than 80 members of Congress on Thursday in support of efforts to offer illegal immigrants a path to citizenship. Wednesday's meeting included strategy sessions on how to influence the immigration debate and ensuring that Salvadoran Americans are fully counted in the 2010 Census.

But participants stressed that the larger purpose was simply to overcome their geographic dispersal, personality differences and longstanding ideological divisions stemming from El Salvador's civil war to convene as a group for the first time.

"We're not here to look for unity, because unity is a romantic dream that is hard to reach," said Salvador Sanabria of Salvadorans in the World, one of the four largest organizations. "We're here to come to this round table without hierarchy to find a consensus about the actions we can take to help our community."

Among the clearest points of agreement was that Salvadoran Americans should insist that any legalization plan adopted by Congress allow about 200,000 Salvadoran illegal immigrants who were granted temporary legal status in the wake of a 2001 earthquake to be the first in line to become permanent legal residents.

Indeed, several participants pointed to the unusual interests of those Salvadorans as an example of why they need to organize as a separate, national Salvadoran American movement.

"We have a separate identity even as we're part of the larger Latino community," said Jose Artiga of the SHARE foundation, which promotes development in El Salvador.

For all the event's optimism, there are some daunting obstacles to transforming the numerical strength of Salvadoran Americans into political clout. According to an analysis of Census data by the Pew Hispanic Center, 47 percent of U.S. residents of Salvadoran descent are not citizens. And 26 percent more are citizens but are still children, leaving only 27 percent who are currently eligible to vote. And it was perhaps telling that much of the discussion at the conference was in Spanish.

Still, many took heart in the political success of Salvadoran Americans in the Washington region. While far more Salvadorans live in California, their influence there is often overshadowed by that state's much larger Mexican American population.

By contrast, its 134,000 Salvadoran immigrants comprise the Washington region's largest foreign-born group. The figure is greater if their U.S.-born children are included.

That might explain why the nation's four highest Salvadoran American elected officials are from Washington. In addition to Gutierrez, they are Arlington County Board Chairman J. Walter Tejada (D), the summit's other co-organizer; Maryland Del. Victor R. Ramirez (D-Prince George's); and Prince George's County Council member William A. Campos (D-Hyattsville), who were also in attendance.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/09/23/AR2009092304494.html

This reflection was written by Laura Davison, a freshman in Journalism at Missouri University. Laura participated in a SHARE delegation this past June with her church Good Shepherd which is located in Kansas City, Kansas.

Here I am, Lord.

Here we are: Ten of us, four adults and six students, riding a bus to El Buen Pastor, a community of about 100 people in central

But before any of us could process anything we are seeing, the bus slows and pulls off the road where a crowd of people waits. Children, mothers with babies and an old man waving a red balloon stood at the gate of the community waiting to greet us. We had arrived at El Buen Pastor.

Is it I, Lord?

It’s easier to forget that

There is nothing subtle about the need in

But the unsettling feelings, though uncomfortable, were necessary. They forced us to reevaluate what is important. And we were forced to look at ourselves and see what we wanted to change about how we treat other people.

The people of El Buen Pastor were rich is so many ways that we are poor. We have never been treated more hospitably. They were willing to give us things they didn’t even have for themselves. When there wasn’t an open pew in mass, some community members left mass and walked several blocks to get chairs so we could sit down. When the water wasn’t running for the shower and toilet in the guesthouse, they immediately began to fix the problem so we could be comfortable. In their homes, they don’t have showers and toilets. They had built the bathroom in the guesthouse so delegations could be more comfortable. It was the little things they did that showed us that we were not visitors whom they had never met before, but rather they considered us family.

I have heard you calling in the night.

In addition to visiting El Buen Pastor, we visited another community near San Salvador called Las Nubes, meaning “The Clouds” in Spanish. This community of 14 houses is nestled on the side of a dormant volcano where low-lying clouds occasionally hang. This mountain is property of a television station, and unbeknownst to the company, these families have lived there for nearly fifteen years. The community at the base of the volcano, San Ramon, had even forgotten people were living here. The people live in shacks of corrugated tin that would look pitiful even in comparison to the modest homes in El Buen Pastor. By our standards, these structures would be unfit for animals. The people of Las Nubes had no electricity, and until recently, no source of water in the village. Last year, the people didn’t even have enough food to feed themselves, so they went down the volcano to ask San Ramon for help. San Ramon is also a poor community. Even so, they have helped feed the people of Las Nubes and build a pipeline to carry water up to volcano once every eight days. This was the poor giving to the desolate.

It’s impossible to see things like this and not be compelled to act.

I will go, Lord, if you lead me.

As we left El Buen Pastor and El Salvador, we left with new friends, new perspectives, but most importantly we no longer felt powerless.

While El Buen Pastor needs financial support that is not the only way to assist them. We learned that our time, our support and encouragement are also much-needed gifts. Solidarity is the most important resource we can give them

The people of El Buen Pastor taught us important lessons of humility, hospitality and hope. And, we, just by listening to their stories, worries and dreams, we were able to validate their lives.

I will hold your people in my heart.

Monseñor Romero Coalition

Press Release

The Monseñor Romero Coalition, of which the SHARE Foundation is a member, wishes to inform the Salvadoran civil society and the international community of the launching of a citizens campaign entitled "MONSEÑOR ROMERO: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND HOPE."

The Monseñor Romero Coalition, of which the SHARE Foundation is a member, wishes to inform the Salvadoran civil society and the international community of the launching of a citizens campaign entitled "MONSEÑOR ROMERO: TRUTH, JUSTICE AND HOPE."

gs, reflections, a small documentary they had made about the massacre and short play they had written.

gs, reflections, a small documentary they had made about the massacre and short play they had written.None of the youth had lived through the Calabozo massacre that happened by

Remembering the past so as not to repeat itself is not just something that people say in theory, it’s something that is very real in El Salvador where many of the people who ordered massacres such as the massacre of Calabazo are powerful government figures who are protected by an amnesty law that does not  allow them to be prosecuted for war crimes. One point that continued to surface throughout the entire commemoration ceremonies was the fact that one of the architects of the Calabozo massacre, Sigfredo Ochoa Perez, is currently the Salvadoran ambassador to

allow them to be prosecuted for war crimes. One point that continued to surface throughout the entire commemoration ceremonies was the fact that one of the architects of the Calabozo massacre, Sigfredo Ochoa Perez, is currently the Salvadoran ambassador to

But the people in the communities such as the Amatitans continue to fight for justice, whether their government supports them or not. And after being present for all the activities it is evident that this struggle is one that is being passed on to the future generations and will not die when the Calabozo survivers do but rather continue on as long as the history of El Calabozo, of El Mozote of the Rio Sumpul and all the other horrible acts of war are being told.

-Laura Hershberger, SHARE Grassroots Solidarity Eduation CoordinatorPhotography captions:

1) Youth at the vigil with a sign that reads: "The youth from Nueva Guadalupe rescueing our historic memory on the 27th anniversary of the massacre, we are remembering our martyrs who will always be in our hearts"

2) Sign with the names of the martyrs being held during the campfire at the vigil

3) Mass being said at the site of the Calabozo massacre, photo taken from the CoLatina